Motivation

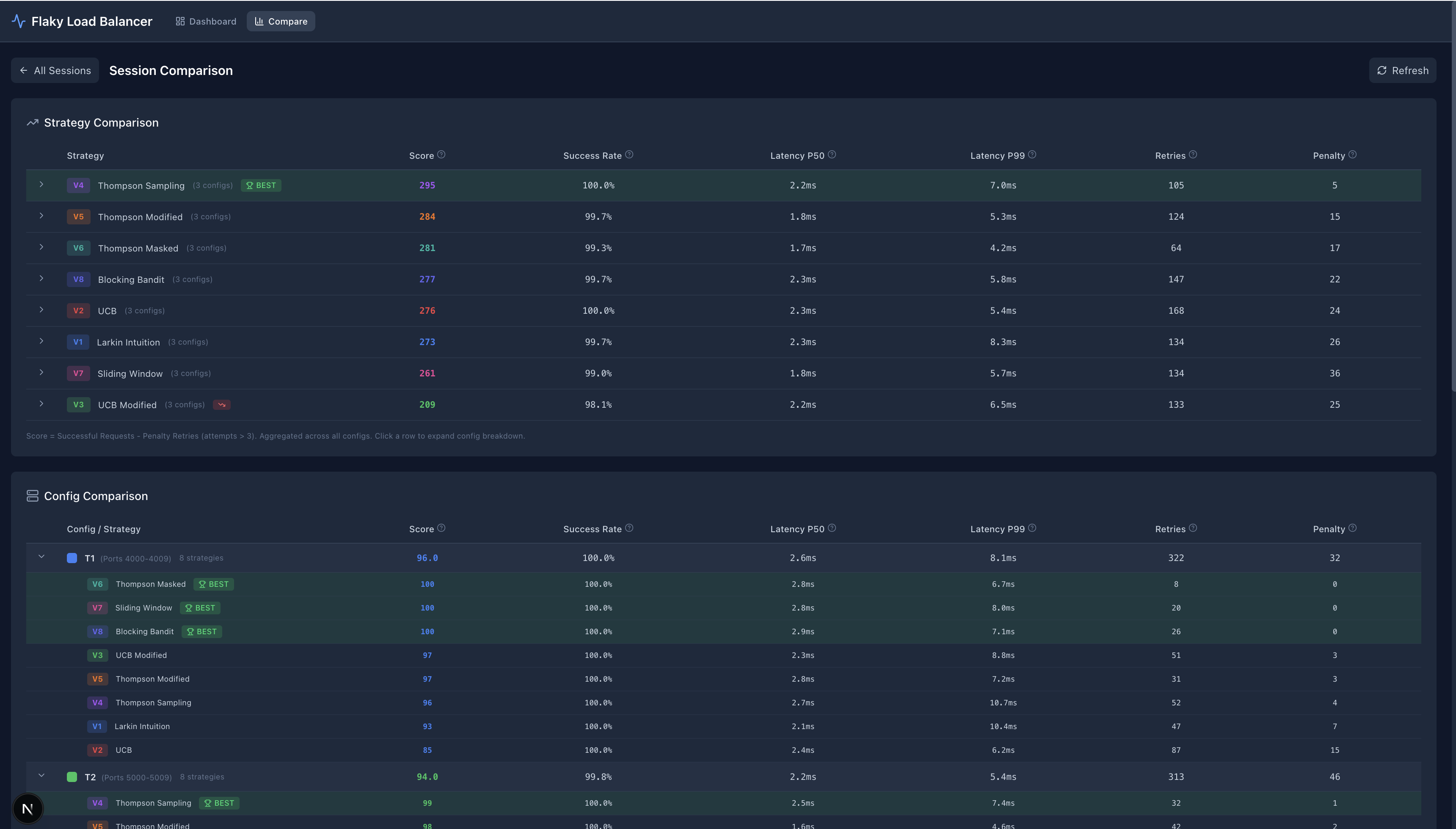

Here is a motivating visual to build up some momentum to read on. This is our dashboard tool to compare various multi-armed bandit strategies. We’ll understand this more thoroughly at the end of this blog post.

Context

Recently, I responded to some recruiters and fielded a couple of interviews.

I generally abhor interviewing. There are parts I absolutely love - meeting new people, learning about new technical challenges, studying up on businesses or industries - but there are also parts I abhor. Getting grilled on usage of the Web Speech API (man oh man was I in the wrong interview) or how to decode a string in 2026 does feel… a bit perplexing. I’ll rant about it on Substack at some point in time.

However! I do genuinely enjoy take homes (as exemplified by Book Brain). Despite often it being a bigger time constraint, and more of a commitment.

This blog post is going to go over a concept and problem that (embarrassingly enough), I hadn’t yet seen before the take home. For more context, I had accepted another offer in the same timeframe, and withdrew from this specific takehome process. It’s unfortunate too because I do genuinely believe the company will be a $10BN company in no time, and the engineering seems fascinating.

While I ultimately withdrew from this interviewing cycle, and sent them only my thoughts on the problem, this blog post is going to talk about a take home question I received from that company. I’m anonymizing the company to keep the sanctity of their interview process.

The company restricted Ai usage during the take, so I did a ton of research / youtube videos. However, for this blog post, some details of implementation will be left to Claude. The repo has documentation and detail included various transcripts between Claude and I. So let’s begin with the problem.

Setup

This blog post is going to focus on the multi-armed bandit problem, which is commonly abbreviated as MAB. There is a lot here, so I won’t be able to cover everything, but I’ll cover the parts that the corresponding Github repo covers.

Multi-Armed Bandit Problem (MAB)

The traditional multi-armed bandit is pretty well encapsulated by a hypothetical situation. I’ll give you the long / fun version, and then I’ll give you an abbreviated Wikipedia version.

Imagine, you wake up.

You live in a beautiful city (let’s say Cincinnati).

But then you realize you have too much money in your pockets. You decide to gamble (i discourage this, especially after seeing how the sausage is made).

So you hit the casino!

However, because it’s Cincinnati, this is a very nice casino. You actually have a chance to win. However, they only have single-armed bandits - commonly known as slot machines! These are unique slot machines, and their underlying probably distributions become more apparent over time.

Despite having too much money in your pockets, you love winning, so you do want to win. Your problem therefore is to figure out the optimal strategy for which machines to play, when to play those machines, how many times to play them, and when you need to switch.

Wikipedia more blandly (but also more succinctly) puts this as:

More generally, it is a problem in which a decision maker iteratively selects one of multiple fixed choices (i.e., arms or actions) when the properties of each choice are only partially known at the time of allocation, and may become better understood as time passes. A fundamental aspect of bandit problems is that choosing an arm does not affect the properties of the arm or other arms.[4]

Stochastic MAB Approaches

Before we go any further, let’s fully dissect this problem.

There are really two main focuses that I covered in code and fully studied up on. I will not be talking about $\epsilon$-greedy approaches, but here are some other resources. We’re actually going to focus on UCB vs Thompson Sampling, which are two methods that work very well. I’ll discuss further below in the implementation about my thoughts about how I modified them to handle the take-home explicitly.

Upper Confidence Bound

The theory behind UCB is that we are trying to optimistically explore. UCB1 is meant to balance the level of exploration vs exploitation.

I am not going to go into the full derivation, but it references something called Hoeffding’s Inequality to build up a framework.

It eventually lets us get to:

\[UCB_i(t) = \bar{x}_i + \underbrace{c \cdot \sqrt{\frac{\ln(t)}{n_i}}}_{\text{exploration bonus}}\]Where:

- $\bar{x}_i$ = empirical success rate of server $i$

- $t$ = total number of requests across all servers

- $n_i$ = number of times server $i$ has been tried

- $c$ = exploration constant (default: $\sqrt{2}$)

Normally, you’ll see this kind of folded up with $c$ being part of the square root, but that exploration bonus was key in my modified UCB approach.

Thompson Sampling

With this approach, the derivation can actually make a bit more sense (in my opinion). It’s also (probably relatedly) the approach I like the most.

We model the process for the specific outcome of the arm $a$ as a Bernoulli distribution. Basically, it means we have a $p$ probability of getting a 1 (in this case, a reward, in our specific case further down - a successful downstream server request). The value 0 has a probably $q = 1 - p$ of occurring.

We can then model this uncertainty about the Bernoulli parameter $p$ as a beta distribution. We’re trying to figure out the probability $p$ for each arm $a$ (or further on as we’ll see, the downstream server).

Think of using our beta distribution as a heuristic for what we actually think about each arm. With Thompson sampling, we’re basically maintaining a best guess distribution for each of the arms and updating it as we go and learn more information. I believe the technical term for this is that we’re using a beta distribution as a prior and our posterior given we are assuming a beta distribution in both cases.

Formally, the beta distribution has a $\alpha$ and a $\beta$ that control the shape of the distribution. They are exponents of the variable and the variable’s complement respectively. So again, this can be written as:

\[f(x; \alpha, \beta) = \text{constant} \cdot x^{\alpha - 1} \, (1 - x)^{\beta - 1}\]Then our logic is pretty straight forward given how we’re modeling this. For every success of the arm, we can update our $\alpha$ with a simple $\alpha’ = \alpha + 1$ and for every failure, we can update our $\beta$ (given it’s modelling the complement) as $\beta’ = \beta + 1$.

A picture is worth a thousand words, so an interactive visualization must be worth at least a million right? This is a Claude generated vanilla JS + Chart.js artifact. I’d recommend autoplaying or doing the Run Thompson Round, but you can also see results by adding success and failures to the various arms. The main point is that you’ll see how our beta distributions should steadily converge to the real $p$ with increasing accuracy.

Multi-Armed Bandit Variants

The situation I described above is really the stochastic MAB. There’s a finite set of arms, and the reward distribution is unknown. As I learned throughout this process, there are many variants and generalizations of this problem. Specifically, these are generalizations where the MAB is extended by adding some information or structure to the problem. Namely:

- adversarial bandits

- this is probably my favorite variant. the notion is that you have an adversary that is trying to maximize your regret, while you’re trying to minimize your regret. so they’re basically trying to trick or con your algorithm.

- if you’re asking yourself (like I did), ok well then why doesn’t the adversary just assign $r_{a,t} = 0$ as the reward function for all arms $a$ at time $t$, well… you shouldn’t really think about it in terms of reward. Reward is relative. We instead want to think about it in terms of regret which I’ll talk more about later. There are two subvariants (oblivious adversary and adaptive adversary), but we’re not going to discuss those - although a very interesting extension is the EXP3 algorithm.

- contextual bandits

- the notion here is that instead of learning $E[r \mid a]$ where again $r$ is the reward and $a$ is the arm you pick, you’re learning $E[r \mid x, a]$ where $x$ is some additional bit of context at time $t$ that you’re exposed to.

- dueling bandits

- an interesting variant where instead of being exposed to the reward, your information is limited to just picking two bandits and only knowing which one is better comparatively… but again it’s stochastic. So you can inquire about the same two arms and it’s very feasible that you’ll get different results for the comparison. The whole notion is that you’re building up this preference matrix. Seems like an incredibly difficult problem.

Bandit with Knapsack (BwK) Variant

I’m going to preempt the reader and discuss another variant, where I’ll spend a bit more time. That model is the Bandit with Knapsack problem.

The original paper is from Ashwinkumar Badanidiyuru, Robert Kleinberg, and Aleksandrs Slivkins. People who I’d love to be an iota as smart as. You can see the paper here. It’s a 55 page paper, and I’d be lying if I said I read past the Preliminaries section. Section 3+ have some heavy math that is over my head.

The problem statement is relatively simple though. Your arms now have resources associated with them that they consume. I honestly think it’s easier to draw it out mathematically and reference the actual paper (also shoutout to alphaxiv, it’s got most of the normal [arvix] features, just with some ai native question answering and highlighting which has been nice).

Formal Declaration

I’d like to state that the paper starts out with the generalized form of many resources being managed and consumed. It makes sense given it’s a professional paper and the general case is more interesting. However, you can imagine $d$ being 1 and that we have a single resource that we’re managing.

So again, we have $X$ finite arms from 1 to $m$. An individual arm can be declared as $x$. Formally, we can say

\[X = \{ 1,\, 2,\, \ldots,\, x, \, \ldots, \,m-1,\, m \}\]There are $T$ rounds (which interestingly enough is known before time in this variant). So $t$ is the round at time $t$ (and one round per time increment).

\[t = \{1,\,2,\, \ldots,\, T-1,\, T \}\]There are $d$ resources where $d \geq 1$ and the $d$ resources are indexed from $i$ from $1,\, \ldots,\, d$. (the $d$ in our specific example is going to be the number of servers still, because each server is its own rate limit).

So the problem now changes because at round $t$ when arm $x$ is pulled we now don’t just get a reward, but we instead get a reward and a consumption vector indicating how much of the resources were consumed. In other words,

\[\left( r_t, c_{t,1}, \ldots , c_{t,d} \right)\]The paper declares this as $\pi_x$ where $\pi_x$ is an unknown latent distribution over $[0,1]^{d+1}$.

Now “latent spaces” have gotten a ton of usage since LLMs blew up, but basically this just means there is some distribution, and it is fixed, but it’s unknown to the learner.

Just to also break down the syntax because $[0,1]^{d+1}$ can be a bit misleading, but this just means

\[[0,1]^{d+1} = \underbrace{[0,1] \times [0,1] \times \cdots \times [0,1]}_{d+1\ \text{times}}\]So it’s really just a vector of length $d+1$ (the +1 is because we have $d$ resources, but then one reward $r$, so it’s kind of a shorthand).

$\pi_x$ is a joint probability distribution over $(r, c_1, …, c_d)$, or \((r, c_1, ..., c_d) \sim \pi_x\)

meaning when you pull an arm, you draw one vector from this distribution.

This of course leads us to budgeting. Each resource $i$ has a budget where $B_i \geq 0$

The overall process stops as soon as we have exhausted ANY resource budget.

Algorithms Presented

The paper presents two algorithms - BalancedExploration and PrimalDualWithBK.

BalancedExploration

At a high level, BalancedExploration tries to explore as much as possible while avoiding suboptimal strategies. It tries to converge to a LP-perfect distribution. LP-perfect here is a LP-relaxation called LP-primal (also LP = linear programming). So basically if they can reduce some of the constraints in this LP-primal approach then they can have an optimal algorithm. This LP-primal not only reduces the constraints, but the LP assumes that we know the average reward for each arm and removes the uncertainty, and it lets us perform fractional tasks rather than full tasks (this gets into the integer programming formulation which is helpful for the second part).

The algorithm is “simple” as the authors put it, but somewhat abstracted. On each phase, it eliminates any mix of tasks that are obviously not LP-perfect. It creates a confidence interval of potentially perfect LP distributions.

Then for each task, it tries to explore that task as much as possible, and gathers the information. It then repeats until it runs out of time or resources.

Transparently, I get it at this level, but I don’t understand the underlying math pinning it. That confidence interval calculation is… unclear to me. And given I don’t even have an implementation for it in my repo (which is the point of this post).

Ah actually! Giving Claude enough context and framing for this, and it does make sense for my repo. It’s still using UCB / LCB for reward and cost respectively, and then forming that as the score. i.e.:

Claude Code: BalancedExploration Explanation

▐▛███▜▌ Claude Code v2.1.17

▝▜█████▛▘ Opus 4.5 · Claude Max

▘▘ ▝▝ ~/Documents/coding/multi-armed-bandit

❯ /clear

⎿ (no content)

❯ Can you explain how the `BalancedExploration` BwK algorithm could be applied here?

⏺ The Balanced Exploration algorithm from the Bandits with Knapsacks (BwK) literature is a natural fit for your load balancer because you

have a resource constraint built into the problem: the retry penalty system.

BwK Problem Mapping

┌──────────────────────┬─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ BwK Concept │ Your Load Balancer │

├──────────────────────┼─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Arms │ Downstream servers (T1/T2/T3 tiers) │

├──────────────────────┼─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Reward │ Successful request (+1) │

├──────────────────────┼─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Resource consumption │ Retries needed (penalty after 3 attempts) │

├──────────────────────┼─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Budget │ Implicit via score formula: success - 0.5 * penalty_retries │

└──────────────────────┴─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

How Balanced Exploration Works

Standard MAB algorithms (like your Thompson/UCB strategies) only track reward (success rate). BwK algorithms track both:

1. Reward distribution: P(success | server)

2. Cost distribution: E[retries needed | server]

The key insight: a server with 80% success rate that usually fails on first attempt but succeeds on retry might be worse than a 70%

success server that either works immediately or fails completely.

Algorithm Sketch

class BalancedExplorationStrategy(BaseStrategy):

def __init__(self):

# Track both success AND retry cost per server

self.reward_estimates = {} # E[success]

self.cost_estimates = {} # E[attempts needed]

self.confidence_bounds = {}

def select_server(self, servers, attempt_number):

# Compute "bang per buck" with confidence bounds

for server in servers:

reward_ucb = self.reward_estimates[server] + confidence_bonus

cost_lcb = max(self.cost_estimates[server] - confidence_bonus, epsilon)

# Key BwK idea: optimize reward/cost ratio

server.score = reward_ucb / cost_lcb

# Balanced exploration: mix greedy + uniform exploration

if should_explore(): # Based on remaining budget

return uniform_random(servers)

return argmax(server.score for server in servers)

PrimalDualWithBK

The difference here is that we basically have a shadow parameter per resource that is the dual vector portion of this. It represents unit costs for resources and then helps balance resource consumption.

This $\lambda$ is our internal or shadow price that indicates how much we’re willing to pay for a given resource.

Primal-dual is different because it’s adaptive to our remaining budget. If we’re burning through resources too quickly, $\lambda$ rises and we do our best to avoid costly servers.

Claude Code: PrimalDual Explanation

⏺ Great question—these are two fundamentally different algorithmic paradigms for BwK.

Core Philosophical Difference

┌────────────────────────────────────────────┬───────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Balanced Exploration │ Primal-Dual BwK │

├────────────────────────────────────────────┼───────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Ratio-based: Optimize reward/cost directly │ Price-based: Learn a "shadow price" for resources │

├────────────────────────────────────────────┼───────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Explore to reduce uncertainty │ Adapt prices based on consumption rate │

├────────────────────────────────────────────┼───────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ UCB-style confidence bounds │ Lagrangian relaxation of constraints │

└────────────────────────────────────────────┴───────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Primal-Dual Intuition

Instead of optimizing a ratio, Primal-Dual converts the constrained problem into an unconstrained one:

Original: maximize E[reward] subject to E[cost] ≤ budget

Primal-Dual: maximize E[reward] - λ * E[cost]

where λ (dual variable) is learned online

The dual variable λ is the shadow price—how much you're willing to "pay" to consume one unit of resource.

Algorithm Sketch

class PrimalDualBwKStrategy(BaseStrategy):

def __init__(self):

self.lambda_price = 0.0 # Shadow price for retries

self.total_penalty_retries = 0

self.total_requests = 0

def select_server(self, servers, attempt_number):

# Pick server maximizing: E[reward] - λ * E[cost]

for server in servers:

reward = self.success_estimate[server]

cost = self.retry_cost_estimate[server]

server.score = reward - self.lambda_price * cost

return argmax(server.score)

def update(self, server_url, success, attempts_used):

# Update reward/cost estimates (standard)

self._update_estimates(server_url, success, attempts_used)

# KEY DIFFERENCE: Update the shadow price

self.total_penalty_retries += max(0, attempts_used - 3)

self.total_requests += 1

# If consuming resources too fast, increase price

target_rate = 0.5 # Expected penalty retries per request

actual_rate = self.total_penalty_retries / self.total_requests

# Multiplicative weights update

self.lambda_price *= (1 + eta * (actual_rate - target_rate))

Take Home Multi-Arm Bandit Variant

The takehome I received had an interesting twist on this. The change is that: you are only penalized for a failing server request after $k$ tries. So you are still trying to maximize your “score” (i.e. reward) but you’re also given some leeway.

It was not until deep research with Claude / ChatGPT that I learned the problem could (I think) best be framed as a BwK problem.

Flaky Server - BwK Framing

For more context with the takehome, the MAB portion was framed as you’re building a load balancer where the downstream servers are flaky and you’re trying to minimize penalties (which are signed after your failing load balancer request). They simply sent a binary (which I actually dislike and think is very sketch to send a binary with no details, certs or signatures, notarization etc). The binary opened up the following:

- 10 ports with Config 1 (constant error rate)

- 10 ports with Config 2 (constant error rate + constant rate limit)

- 10 ports with Config 3 (constant error rate + complex rate limit)

Approach

Aggressively Inspecting the Binary

No fucking way am I blankly running a binary on my personal computer.

I am familiar with some basic CLI tools for inspecting binaries (otool, strings, xattr from the Dropbox days). However, this was something that I freely threw at Claude with explicit instructions not to run the binary and not to tell me anything about the underlying implementations of the load balancer config implementations (I’ll get to the de-compilation step in a bit).

I also knew that for all commands actually starting the load balancer binary that we would be running them in a restricted mode using sandbox-exec which I hadn’t stumbled upon until this project. The blog i just linked does a fantastic job, so you should feel comfortable giving it some site traffic and peeking into that one. TLDR is it’s a way to run a binary in a sandboxed environment so that it only has permissions to various resources that you permit.

All of this looked good, so I was onto the actual implementation.

Load Balancer

This was obviously the meat of the problem and the most fun to reason and think about. Probably because it was the most math / stats intensive. I wrote a couple of versions myself, tried and saw the failures (Claude found bugs with how I was calculating the beta distributions variance for example) and kept iterating. It’s the part of the code I know the best and I can walk through the various implementations.

The later versions where we get into the BwK approaches (v6 - v8) are implementations by Claude, but still interesting to see how they perform relative to the original ideas.

At this point, I’m pretty burnt on this project and I’m technically on vacation, so I am going to summarize and leave it as an exercise to the reader to investigate the code and understand the underlying logic

These versions are all basic MAB approaches, not BwK specific.

| Code Version | Method | Description |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | Larkin Intuition | We still model things as a Beta distribution. We have a DISCOVER_LIMIT. While we’re in DISCOVER_MODE, we select the arm / server with highest beta variance, and fire off attempts to that server. If that fails, we re-evaluate. We continue until we fail. After the discover limit, then we statically pick the best server to send requests to. |

| V2 | Vanilla UCB | This is the UCB method described above. We first prioritize any untried servers (since technically they have an infinite UCB score). Then for each server, we calculate the UCB score using the formula: \(UCB = \text{success_rate} + \sqrt{\frac{2 \ln(\text{total_requests})}{\text{num_attempts}}}\) |

| V3 | Adjusted UCB | Very similar to the above however this type we play games with our exploration constant. It’s no longer $\sqrt{2}$, it’s 3 (chosen arbitrarily, just bigger than $\sqrt{2}$) for the first three attempts and then 1 after that when we’re starting to get penalized. |

| V4 | Vanilla Thompson Sampling | What we described above, we pick the server with the highest $p$ and then we go from there. Either way if it’s a success or a failure, we update our $\alpha$ and $\beta$. |

| V5 | Modified Thompson Sampling | In a somewhat similar game to the modified UCB, we scale alpha and beta based on the number of requests to encourage exploration. We use an exponential decay and if we’re at 3 attempts or more, we do not scale at all and just revert back to normal TS. Our scale_factor then becomes max(2, total/variance_scale) / total where total = alpha + beta. We then multiply $\alpha$ and $\beta$ by those coefficients. |

These approaches in honesty were CC generated, but are rate limited aware and targeted at BwK approaches.

| Code Version | Method | Description |

|---|---|---|

| V6 | Thompson Masked | A slight discrepancy from the original Thompson Sampling. Here 429s which indicate that we have been rate limited. We exclude rate limited servers from the selection pool. Note, we also indicate a server as being rate-limited if we’ve gotten a 429 in the past second. The big notion is that 429s are treated as different than failures. We do not update $\beta$ when we get one, we instead just indicate it’s been rate limited. If all of our servers are rate limited, we get the server that is most likely to expire soon. This is probably best for Config Type T2. |

| V7 | Sliding Window | Here given that we have the notion of temporal and dynamic rate limiting, we only remember a set amount of requests / history. I chose 30 basically arbitrarily. Again, perhaps ideally we could learn the rate limits and dynamically adapt this. Our $\alpha$ and $\beta$ params are only updated based on the set history. |

| V8 | Blocking Bandit | And here is the adaptive cooldown / blocking that V7 was lacking. The difference is now if we hit a 429 we start to exponentially increase the wait time to block the incoming requests from going to a server that we know is rate-limited. |

Simulation Harness

The simulation harness is almost entirely vibe-coded but basically sends requests to our load balancer at the prescribed rate of 10 RPS. For more information, I would check the flaky-load-balancer/flaky_load_balancer/harness.py file out. It’s on GH here.

Dashboard

The dashboard was a fun vibe coded application that is a NextJS app. There’s a decent amount of functionality here, so I’ll cover some of the highlights. This NextJS project is meant to summarize and compare the results from various strategies (V1-V8) against the various config types (T1-T3). It also has a comparison route that compares all of them for a given run.

It connects and listens to the FastAPI server (basically to our load balancer) so that we get SSE streams for things like the heartbeat, metrics, and connected state. So what I would suggest is running make harness and that will start your FastAPI load balancer, start the dashboard, start the downstream flakyservers binary, and then start firing off requests.

Here is a demo:

And furthermore, here are some screenshots from the comparison page:

Conclusion

So! What were the results?

Unsurprisingly, our Thompson Modified seemed to do the best on T1, the Sliding Window somewhat surprisingly did the best on T2 (probably because the underlying binary is sinusoidal and there was some benefit about the cadence and the window being used). Finally, for T3 the Blocking Bandit or Thompson Masked seemed to do the best.

There’s a lot more I could talk about here, but this has already spilled over on the time budgeting so I will end here. If interested, feel free to reach out!