First of all, I want to clarify that I am by no means an expert in anything quantum. I have no PhD. The farthest I ever got was taking Physical Chemistry (PChem) I and II in college. I have not worked at Google, or a leading quantum company. I haven't ever run a program on quantum hardware (although I (and you) should).

That being said, it's always been something I've loved and been captivated by. PChem was one of my favorite classes in college. I still distinctively remember sitting in the second floor of Science Center with Kathleen Howard. A couple of my brilliant classmates were Aditi Kulkarni (my lab partner for most of it), Brian Gibbs, and Jacob Kirsh. All brilliant and now either all getting PhDs, MDs, or some other impressive feat. Kirsh is even getting his PhD in biophysical chemistry at Caltech now. Fun quantum related note, one of my friends parents is also CEO of a major (public) quantum computing company.

PChem I and PChem II gave me a very early tease into quantum mechanics and the blossoming physics behind it. PChem did not, however, give me a good grasp of quantum algorithms and computing. The closest I got would have had to be in my Algorithms class at Swarthmore with Josh Brody. He called out and gave the pseudocode for Shor's Algorithm, a quantum approach for factoring prime numbers. This obviously has huge repercussions for encryption and cyber security.

Regardless, this will hopefully be a review of some fun things I learned back in PChem, as well as looking at it a little bit more from a true quantum computing angle.

Motivation

In this post, we’re going to:

- Review some quantum physics fundamentals

- See how those apply to the quantum computing landscape

- Look at some very basic visualizations and ideas

- Explore some public companies and latest research that I’m interested in (just bullish in the space)

Driving Motivation

Here’s where we’re going to eventually get to in terms of understanding:

Hint: It's interactive! Try playing around with the demo below!

We’re eventually going is building the application here which basically simulates some of the math behind the Paul trap.

Quantum Physics Fundamentals

What is Quantum Mechanics?

I will not give my layman’s answer and instead point directly to the Department of Energy, which offers a surprisingly well put synopsis.

Quantum mechanics is the field of physics that explains how extremely small objects simultaneously have the characteristics of both particles (tiny pieces of matter) and waves (a disturbance or variation that transfers energy). Physicists call this the “wave-particle duality.”

The particle portion of the wave-particle duality involves how objects can be described as “quanta.” A quanta is the smallest discrete unit (such as a particle) of a natural phenomenon in a system where the units are in a bound state. For example, a quanta of electromagnetic radiation, or light, is a photon. A bound state is one where the particles are trapped. One example of a bound state is the electrons, neutrons, and protons that are in an atom.

To be “quantized” means the particles in a bound state can only have discrete values for properties such as energy or momentum. For example, an electron in an atom can only have very specific energy levels. This is different from our world of macroscopic particles, where these properties can be any value in a range. A baseball can have essentially any energy as it is thrown, travels through the air, gradually slows down, then stops.

At the same time, tiny quantized particles such as electrons can also be described as waves. Like a wave in the ocean in our macroscopic world – the world we can see with our eyes – waves in the quantum world are constantly shifting. In quantum mechanics, scientists talk about a particle’s “wave function.” This is a mathematical representation used to describe the probability that a particle exists at a certain location at a certain time with a certain momentum.

The world of quantum mechanics is very different from how we usually see our macroscopic world, which is controlled by what physicists call classical mechanics. Quantum mechanics grew out of the tremendous progress that physicists made in the early 20th century toward understanding the microscopic world around us and how it differed from the macroscopic world.

As with many things in science, new discoveries prompted new questions. Prior to this time, scientists thought that light existed as an electromagnetic wave and that electrons existed as discrete, point-like particles. However, this created problems in explaining various phenomena in physics. These include blackbody radiation—the emission of light from objects based on their temperature. Quantum mechanics also helped explain the structure of the atom. It helped make sense of the photoelectric effect, which involves how materials emit electrons when those materials are hit with light of certain wavelengths. By explaining how things can be both particles and waves, quantum mechanics solved these problems.

History

I’m going to start with some history because it’ll set the scene. Obviously, this could be a whole semester long course at a collegiate level, so this is going to be the heavily Sparknotes version.

Tangent on When We Cease to Understand the World

Also the history is a bit topical given I’ve been reading When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamin Labatut. It’s a beautifully written book and the section of the book I’m currently on discusses at length Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger. I’d highly recommend it.

That being said, the book is creative non-fiction, which means that a lot of the stories are exaggerated or have fiction sprinkled in to entice and entertain the readers. That’s all well and good,, but makes for a frustrating reading experience sometimes given I’m googling if things really happened.

For example, the quantum physics portion starts by telling the story of how Heiseinberg interrupted Schrödinger’s lecture. As far as I can tell, that just did not happen. I could not find any trace of it online. I even asked Perplexity.

Regardless, let’s move on.

Timeline

This Wikipedia article, Timeline of Quantum Mechanics, is going to do a far far better job then I ever will.

That being said! It’s 2025, and we can do some more fun and interactive visualization. Check it out below.

Feynman in 1981

“I therefore believe it’s true that with a suitable class of quantum machines you could imitate any quantum system, including the physical world” - Richard Feynman (1981)

The original paper can be found here:

This was a pretty seminole keynote talk where Feynman states that the natural world is by nature, driven by quantum mechanics. How such can we interrupt our physical world - especially the quantum mechanics of it - using a classical computer. Feynman basically says that you cannot accurately do this.

He cites a thought experiment and study that he does related to photon polarization. I kind of got lost here, so I copied and pasted this portion into Claude and asked for a summary. I’ll post that now because it’s clearer than my writeup.

The Basic Setup:

A photon passes through a piece of calcite crystal The calcite splits the photon into two possible paths:

An “ordinary” ray (O) An “extraordinary” ray (E)

When you measure, you always find the photon in exactly one path (never split between them)

The Two-Calcite Experiment:

Place two calcites in sequence, with the second one rotated at an angle φ relative to the first This creates four possible paths: O-O, O-E, E-O, and E-E The probability of which path the photon takes depends on the angle φ

The Key Quantum Mechanical Result:

When two observers measure photons from the same source at angles differing by 30° Quantum mechanics predicts (and experiments confirm) that they will get matching results 75% of the time (cos²30° = 3/4)

The Classical Impossibility: Feynman shows why this result cannot be reproduced by any classical system:

In a classical system, each photon would need to have some “hidden” properties that determine how it behaves at each angle He demonstrates this using a clever diagram showing all possible patterns of O/E results at different angles When you analyze all possible classical patterns, the maximum correlation you can get at 30° is 2/3 (about 67%) This is less than the quantum mechanical result of 75%

This is a concrete demonstration of why quantum mechanics cannot be simulated by classical probabilistic systems - quantum systems can produce correlations that are stronger than any possible classical system could achieve. This became known as one of the clearest demonstrations of quantum “weirdness” and the impossibility of local hidden variable theories. This experiment is particularly powerful because:

It’s a clear, measurable difference between quantum and classical behavior The mathematics is relatively simple (just comparing 75% vs 67%) It’s been experimentally verified many times It demonstrates that quantum mechanics isn’t just strange in theory, but produces measurably different results from any possible classical system

The paper is renown because it is one of the first arguments that quantum simulation might be a key unlock for better understanding quantum mechanics itself.

Feynman in 1985

Feynman also had a more specific quantum computing article that he published in 1986. You can check that one out here:

This one I have not read and definitely have not fully grokked. Feynman introduced a novel architecture for how to build a quantum computer. This is true electrical engineering, proposing the construction of an AND and NOT gate, as well as FAN OUT andEXCHANGE gates. He also introduces a CNOT gate (controlled not).

But… I’m going to leave it there. And we’re going to move to some more exploration about current practices.

I’ll leave it as an exercise to the reader to explore more about Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle or Schrödinger’s Wave Equation. I would highly recommend at least checking out the last link to the wave equation. The wiki article is great.

Bridge to Quantum Computing Today

So given the public markets interest, as well as my long term interest in the subject matter, I thought it would be interesting to look at the job description for companies like Ionq or Google and what the job descriptions look like for those companies - knowing full well that I’ll never end up working there given my current pedigree.

Basically there are two main frameworks (in Python) for quantum computing circuit design and simulation - cirq and qiskit.

Before we get there though, I want to cover some of the basic terminology:

Terminology

qubit

This is the quantum analogue for the classic bit. The two basis states are written as \(\vert0\rangle \text{ and } \vert1\rangle\). Most importantly, the qubit can be in \(\vert0\rangle\) or \(\vert1\rangle\) or a linear combination of both states. This is commonly referred to as superposition.

Qubit states are generally represented as \(\psi = \alpha \vert 0\rangle + \beta \vert 1\rangle\) where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are the probability amplitudes for each basis state.

entanglement

A special connection between qubits, where they become correlated and share the same fate. This is a core principle of quantum computing and basically part of the reason that with true quantum computing (i.e. superconducting circuits), these traits are only available or detectable at such low temperatures.

Cirq

This is a popular one that was built and designed for Google’s quantum hardware. Here’s a link to cirq.

Developed by: Google

Primary Purpose: Cirq is designed to build, simulate, and execute quantum algorithms on Google’s quantum processors (like Sycamore). It is optimized for NISQ (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum) devices and focuses on fine-grained control of quantum circuits.

Key Features:

- Circuit-Level Control: Cirq allows precise control over quantum gates and qubits, making it ideal for experiments requiring hardware-level customizations.

- Noise Simulation: Provides tools to model and simulate noise in quantum computations.

- Workflow: Circuits are created using cirq.Circuit and executed on simulators or real devices via Google’s cloud services.

- Compatibility: Works well with Google’s quantum hardware, but also supports other simulators.

- Gate Sets: Offers native gate sets for Google’s quantum hardware, such as sqrt(X) and CZ.

Qiskit

IBM, however, has been working on this problem for even longer. qiskit has been around longer and is more widely adopted, and a bit more generally open source.

Developed by: IBM Primary Purpose: Qiskit is a comprehensive quantum computing framework that supports creating quantum circuits, simulating them, and running them on IBM Quantum devices.

Key Features:

- Multi-Backend Support: Qiskit can run circuits on IBM’s cloud quantum hardware and multiple local simulators.

- Algorithm Libraries: Comes with high-level modules for quantum algorithms, machine learning, chemistry, and optimization.

- Transpilation: Qiskit includes transpilers to optimize quantum circuits for specific hardware constraints.

- QASM Integration: Supports OpenQASM, a low-level quantum assembly language.

- Extensive Ecosystem: Libraries such as Qiskit Aqua, Qiskit Ignis, Qiskit Terra, and Qiskit Aer add specialized functionalities for quantum algorithms, error mitigation, circuit optimization, and simulation.

Future Work

A future pet project that I want to accomplish is implementing and running Grover’s Algorithm or Shor’s Algorithm utilizing qiskit and IBM’s free tier services.

It’s a non trivial amount of work, but for future me, here are some good links:

For what it’s worth, I started poking around some here: quantum exploration github.

Public Companies and Latest Research

Also since the time of writing this article there's been a ton of news in the markets about quantum. Various quantum stocks have been on a tear since late last year. There was even more recent news this year after CES (Consumer Electric Show) when Jensen Huang (CEO of Nvidia) made a comment about quantum computing that we're probably 15-20 years out. I think I probably agree with that. Markets reacted accordingly and that's fine. I'm not here to talk about the stocks, I'm here to talk about the underlying technology because I'm a long believer, and I think it's good to know about some of the more recent news trends like Willow.

This section is going to be biased. I am most familiar with traditional superconducting, and this blog is selfishly for me to learn (and share) with others. As a result, I’m going to dive deeper into the trapped ion approach compared to the other sections.

Ionq

Main Approach: Trapped Ions (atomic qubits)

Trapped Ions

So the basic principle here is we’re using ions that are trapped in electric fields to store and process information.

Ions are first isolated and trapped using electromagnetic fields in a vacuum chamber. This trapping ensures they are well controlled and isolated from environmental noise, which could disrupt their delicate quantum states.

Each ion then represents a qubit. Lasers are then used to carefully manipulate the energy levels of these ions, effectively writing and reading information onto the qubits.

A crucial element of all of these quantum designs is entanglement. In trapped-ion systems, this is achieved by using carefully designed laser pulses.

Sidebar

This is kind of a wildly different approach, but very interesting. The quantum state of the ion (i.e. i think basically just the energy level) is representing the qubit, and then we’re just putting the ion in a superposition with the lasers. So it’s almost a different way of using a qubit.

How are these ions trapped?

This is the core of how those ions are trapped. It’s called a Paul Trap (but it’s the same thing as a quadrupole ion trap).

It’s basically like a tiny electromagnetic cage that is holding these ions. They’re almost entirely isolated from their environment which is great because quantum computing is very sensitive to noise and environment. The ions are held incredibly still because the lasers need to very specifically excite / impose desired states on these trapped ions. And finally, thanks to these two points, trapped ions can maintain their quantum states for relatively long periods. This is known as coherence and is a big conversation in quantum computing.

That electromagnetic cage or well is basically created from the oscillating electric fields. The math behind this is very interesting and is a of a famous variety. They’re solutions to Mathieu’s differential equation

\[\begin{align} \boxed{\frac{d^2 y}{dx^2} + \left( a - 2q \cos(2x) \right)y = 0} \end{align}\]With respect to the Paul trap, we have this version.

\[\begin{align} \boxed{\frac{d^2 u}{d\xi^2} + \left[ a_u - 2q_u \cos(2\xi) \right]u = 0} \end{align}\]where

\[\begin{align} u & \text{ - represents the } x, y, \text{ and } z \text{ coordinates} \\ \xi & \text{ - a dimensionless variable given by } \xi = \frac{\Omega t}{2} \\ a_u, q_u & \text{ - dimensionless trapping parameters} \\ \Omega & \text{ - the radial frequency of the potential applied to the ring electrode} \end{align}\]The math here is above my paygrade. I start to lose the understanding. However, it’s 2025 and we can take some advantage of LLMs here.

Decomposing the Math Behind a Paul Trap

So again, let’s start here:

\[\begin{align} \frac{d^2 u}{d\xi^2} + \left[ a_u - 2q_u \cos(2\xi) \right]u &= 0 \\ \end{align}\]We can apparently relate \(\xi\) to time \(t\) (this is kind of just given from Wikipedia but i think it’s a relationship of \(\xi\) that’s unstated).

\[\begin{align} 2 \xi &= \Omega t \\ \xi &=\frac{\Omega}{2} t \\ &\therefore \\ \frac{d\xi}{dt} &= \frac{\Omega}{2} \\ \end{align}\]Then - like Wikipedia says - we can apply the chain rule. They don’t cover this, but I think this is what they were going for:

\[\begin{align} \frac{d^2u}{d\xi^2} = \frac{d}{d\xi}\left( \frac{du}{d\xi} \right) = \frac{d}{d\xi} \left( \frac{du}{dt} \frac{dt}{d\xi} \right) = \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{du}{dt} \right) \left(\frac{dt}{d\xi} \right) ^2 = \frac{d^2u}{dt^2}\left( \frac{dt}{d\xi} \right) ^ 2 \end{align}\]This legit took me quite a bit. And yes it’s almost certainly because I forgot the chain rule and product rule. So let’s just clarify this portion specifically

\[\begin{align} \frac{d}{d\xi} \left( \frac{du}{dt} \frac{dt}{d\xi} \right) = \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{du}{dt}\right) \left( \frac{dt}{d\xi} \right) ^ 2 \label{1} \\ \end{align}\]So specifically here \(\frac{du}{dt} \frac{dt}{d\xi}\), let’s apply the product rule

\[\begin{align} f(t) = \frac{du}{dt} &, g(\xi) = \frac{dt}{d\xi} \\ \frac{d}{d\xi} \left( f(t) g(\xi) \right) &= \frac{df(t)}{d\xi} g(\xi) + f(t)\frac{dg(\xi)}{d\xi} \\ \end{align}\]Then chain rule:

\[\begin{align} \frac{df(t)}{d\xi} = \frac{df}{dt}\frac{dt}{d\xi} = \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{du}{dt} \right) \frac{dt}{d\xi} = \frac{d^2u}{dt^2} \frac{dt}{d\xi} \end{align}\]Ah ok beautiful so now that we have that remember we’re doing the product rule, and we really are coming back to this:

\[\begin{align} f(t) = \frac{du}{dt} , g(\xi) = \frac{dt}{d\xi} \\ \frac{d}{d\xi} \left( f(t) g(\xi) \right) = \frac{df(t)}{d\xi} g(\xi) + f(t)\frac{dg(\xi)}{d\xi} \\ \end{align}\]That second term \(f(t) \frac{dg(\xi)}{d\xi}\) actually falls out because \(\frac{d}{d\xi} \left( \frac{dt}{d\xi} \right) = 0\) because \(\frac{dt}{d\xi} = \frac{2}{\Omega}\).

So then if we go back we get how

\[\frac{d}{d\xi} \left( \frac{du}{dt} \frac{dt}{d\xi} \right) = \frac{d^2 u}{dt^2} \left( \frac{dt}{d\xi} \right)^2.\]From here, recall

\[\begin{align} \frac{dt}{d\xi} &= \frac{1}{d\xi / dt} = \frac{1}{\Omega / 2} = \frac{2}{\Omega} \\ \frac{d^2u}{d\xi^2} &= \frac{d^2}{dt^2}\left(\frac{2}{\Omega}\right)^2 = \frac{4}{\Omega^2} \frac{d^2u}{dt^2} \\ \frac{d^2u}{dt^2} &= \frac{\Omega^2}{4}\frac{d^2u}{d\xi^2} \\ \frac{d^2u}{d\xi^2} &= \frac{4}{\Omega^2} \frac{d^2u}{dt^2} \end{align}\]Ok 😓 so we finally substitute Equation 24 back into our Equation 2.

So let’s see what that gives us

\[\begin{align} \frac{d^2 u}{d\xi^2} + \left[ a_u - 2q_u \cos(2\xi) \right]u &= 0 \\ \frac{4}{\Omega^2} \frac{d^2u}{dt^2} + \left[ a_u - 2q_u \cos(2\xi) \right]u &= 0 \\ \end{align}\]Now Wikipedia plays a little bit of a trick. They say multiply by \(m\) but in reality, I think we multiple by \(\frac{m\Omega^2}{4}\). So let’s do that to cancel some terms.

\[\begin{align} \frac{4}{\Omega^2} \frac{d^2u}{dt^2} + \left[ a_u - 2q_u \cos(2\xi) \right]u &= 0 \\ \frac{m\Omega^2}{4} \left( \frac{4}{\Omega^2} \frac{d^2u}{dt^2} + \left[ a_u - 2q_u \cos(2\xi) \right]u \right) &= 0 \\ \boxed{m \frac{d^2u}{dt^2} + \frac{m\Omega^2}{4} \left( a_u - 2q_u \cos(\Omega t)\right) u} &= 0\\ \end{align}\]Ok so far, so good. The next part does get pretty gnarly.

Here’s what Wikipedia says:

By Newton’s laws of motion, the above equation represents the force on the ion. This equation can be exactly solved using the Floquet theorem or the standard techniques of multiple scale analysis.[8] The particle dynamics and time averaged density of charged particles in a Paul trap can also be obtained by the concept of ponderomotive force.

I’m not going to burn more time on that for the time being. It references the Floquet Theorem which I have never studied or heard of.

Here’s a screenshot of the math, but just check it out and dive in from Wikipedia yourself. Oh wait yeah I’ll pull the professor line, “I leave these derivations as an exercise to the reader” - any Swat professor.

However, the key takeaways are this:

\[\begin{align} a_x &= \frac{8eU}{m r_0^2 \Omega^2} \\ q_x &= - \frac{4eV}{m r_0^2 \Omega^2} \\ q_x &= q_y \\ a_z &= - \frac{16eU}{m r_0^2 \Omega^2} \\ q_z &= \frac{8eV}{m r_0^2 \Omega^2}. \\ \end{align}\]Note! \(q_x = q_y\).

So in layman’s terms really, this is what these terms represent:

- \(a_x\) and \(a_z\)

- these are dimensionless DC parameters in the x and z directions

- they come from static DC potential

- \(a_x\) represents the x direction. note, it’s positive meaning that it’s a restoring force toward the center

- \(a_z\) represents the z direction. note, it’s negative meaning that it’s a repelling force (opposite of x and y direction).

- THis is because in a Paul trap, the potential must satisfy Laplace’s equation so we need these opposite signs

- \(q_x\) , \(q_y\), and \(q_z\)

- these are dimensionless RF parameters (oscillating RF potential)

- describe how time-varying RF field influences ion motion in each direction

- \(q_x\) represents x direction, neg meaning oscillating RF field influences with alternating restoring and repelling

- \(q_x = q_y\) save some keystrokes, this means the same

- \(q_z\) represents z direction and becuase it’s positive means that the RF potential creates an alternating axial force to complement the DC potential

So in other words,

- DC parameters (\(a_x\) and \(a_z\)) come from static voltage \(U\)

- RF parameters (\(q_x\) , \(q_y\), and \(q_z\)) come from oscillating voltage \(V\)

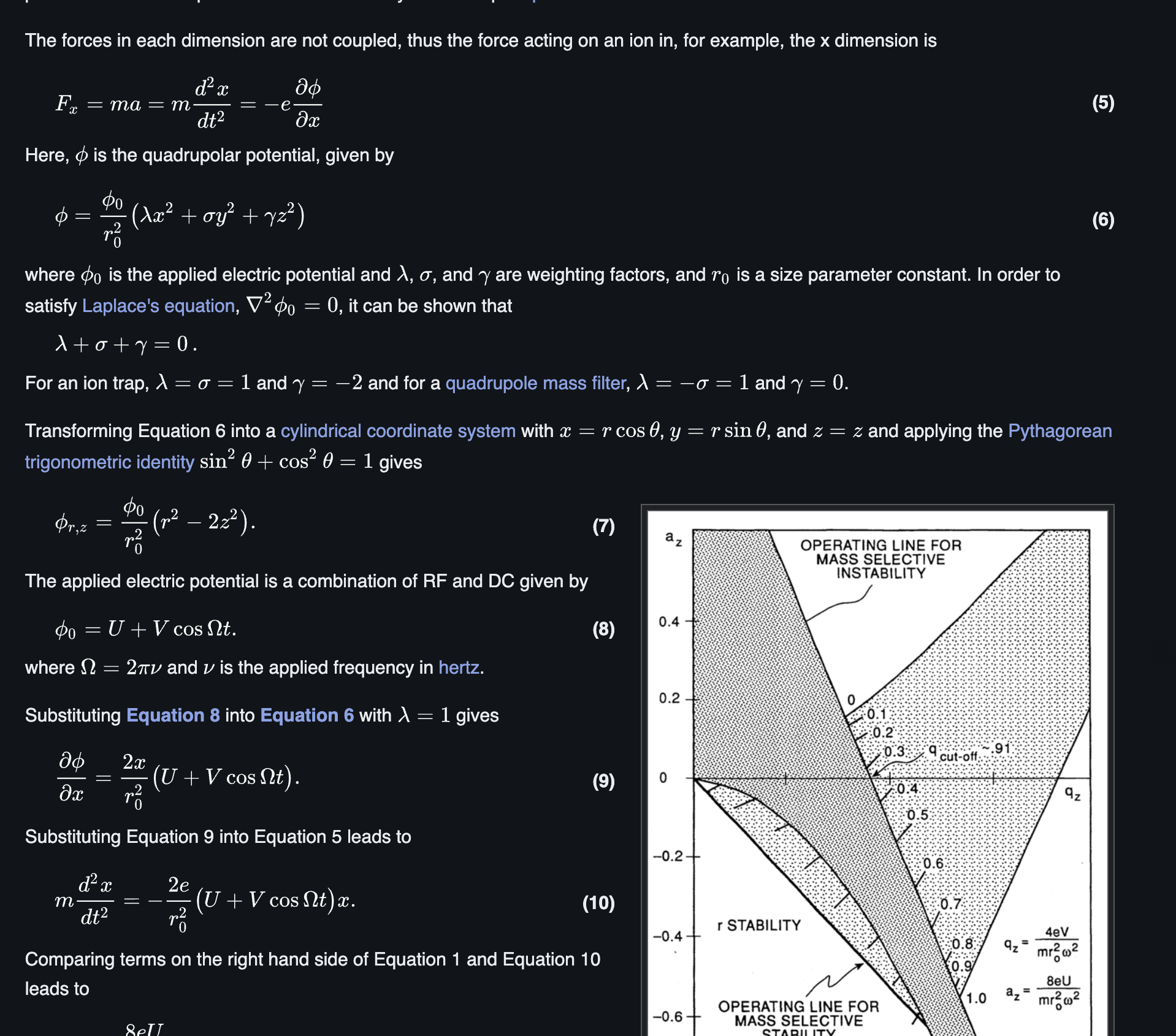

Note!! This whole thing means that for STABLE trapping, the parameters must lie in a certain regions of the $(a, q)$ - plane. The demonstration below will help with this.

Visualizations

So what does this really mean? How can you experiment with this? Again, I’m going to show some excerpts but going to lean on ~ObservableHQ here~. Ok so I was going to go with Observable but man that syntax absolutely sucks. I just fired up a quick Vite project and made a separate repo, and deployed that to Vercel. You can also play around with this here: https://ion-trap-visualizer-prrb.vercel.app/.

It's interactive! Try playing around with the demo below!

I’m not going to say that the code is 100% correct, and Claude did help a bit, but the underlying mathematical principles seem to be sound, and that’s g ood enough for me. For what it’s worth, both Claude and ChatGPT kind of struggled to get the initial values correct. They would come up with starting values saying that these were the “optimal” params for an ion trap (optimal obviously being subjective) but then the visualization would display it as the ion leaving.

However, it did a lot of things well like grabbing a realistic electron mass as well as ion mass.

Big Challenges

I’m not going to go into details here, but major challenges are:

- Scalability (true of most)

- Gate speed

- While longer coherence times, the operations can be slow. A common misconception is that trapped-ion quantum computers are slow because ions are heavy. That’s not true. They’re limited mainly by the speed of laser interactions, not the physical movements of ions. Ions are heavier than electrons but their physical movement isn’t the primary cause for drag.

- Ion heating

- Environment can cause excitement of gates

- Trap Fabrication

- These ion traps require very specific design and fabrication

My opinion

I’ve been a long believer in quantum computing and in specifically IONQ. I know there’s been hype about Willow and other companies but I believe that Ionq with this specific approach is one of the leaders in the field.

Main Approach: Superconducting circuits

Google (and Rigetti) takes a different approach than trying to do trapped ions and instead uses superconducting circuits. They fabricate tiny circuits on chips cooled to near zero. These circuits then behave like artificial atoms with quantized energy levels - the energy levels basically representing our \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) from earlier.

Instead of lasers, Rigetti uses microwaves to manipulate the energy levels of the superconducting qubits, allowing for gate and qubit entanglement.

As a result, they have gate speeds that are up to 10,000 times faster than trapped ion systems.

Willow

I desperately want to explore this, but I have already far over allocated my time budget on this article. As a result, I’ll cover this in another section.

Rigetti

Main Approach: Superconducting circuits

Superconducting Circuits

I’m not going to dive much deeper than this for this section, just given the amount of time I’ve already burned.

DWave

Main Approach: Quantum annealing

Just given the amount of time I’ve already burned on this ad-hoc, meant-to-be-a-quick-weekend-writeup blog, I’m not going to cover quantum annealing. I’m not familiar with it. So once again, I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader.

Miscellaneous

If curious, I sadly don’t have my PChem notebook or binder given they burned down with my Dad’s house (or I might have given it to some of the younger tennis guys 😬), but I did manage to find part of the first homework that I turned in for one of my additional problems for PChem.

Conclusion

Thanks for reading all! If any questions, concerns, or errors on my part, feel free to email me!