Have you heard of cryptocurrencies? So has the rest of the world. Why not make your updates a little easier?

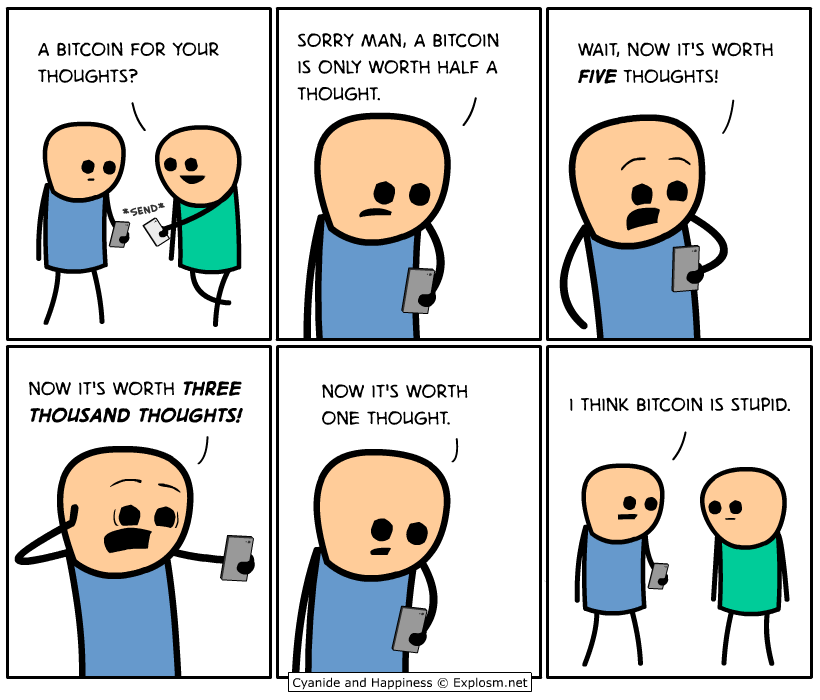

The above image isn’t pertinent to the blog post at all, but I thought it was hilarious and slightly indicative of the lack of knowledge about the actual underlying tech behind a lot of these cryptocurrencies. It’s actually a play on a 1995 Dilbert comic strip that made the same joke but with SQL databases lol. Also don’t get me wrong I barely understand any of the tech behind the coins.

Recently, my roommate and Chicago legend Will and I have recently (like everyone in the world) pretty intrigued by cryptocurrencies. We follow the markets pretty closely and at one point, Willy brought up the good point that it probably wasn’t healthy if we were checking this all the time.

He made a good point. There’s a difference between being invested in something and having your life dependent on it. I thought about some ways that we could simplify this. After learning about cronjobs at work, I figured this is an area where it could come into play. I set out to set up automated daily text alerts with the cryptocurrencies of our preference.

As always, if you don’t care about the blog (totally fine), you can check out the code here!

CoinMarketCap

Unsurprisingly with the boom of cryptocurrencies, there was a couple of strong APIs that opened up for grabbing cryptocurrency data. Most notably, GDAX has a really strong API. They care about their API because you’re able to trade through the API which means… automated trading and algos. Huh that sounds so familiar…

However, I wasn’t really trying to trade. I just wanted information. The best site that I’ve found to check a ton of different cryptocurrency information is Coin Market Cap. Really great website - doesn’t have such interesting graphics as a depth chart which GDAX promotes, but definitely has close to live prices.

Installation for CoinMarketCap API

The API is pretty basic, but still has some decent functionality. You can simply pip install the package like so:

pip install coinmarketcap

Again, the functionality is pretty limited, but essentially you just want to grab the market with

>>> market = coinmarketcap.Market()

Then from here, you can grab the ticker with a certain currency. It defaults to USD though so normally just saying

>>> crypto_market_info = market.ticker()

This is going to grab a list of dictionaries of the top 100 cryptos organized by marketcap. This is the default. If you actually pass in market.ticker(limit=0) then you grab all of the cryptos that are listed on coinmarketcap (hint: this is too much). You can also pass in a currency if you want to observe the stats in a different currency.

The dictionaries for each crypto are filled with a decent amount of information. The keys are as follows:

>>> market_info_btc_dict.keys()

[u'market_cap_usd', u'price_usd', u'last_updated', u'name', u'24h_volume_usd', u'percent_change_7d', u'symbol', u'price_btc', u'rank', u'percent_change_1h', u'total_supply', u'cached', u'max_supply', u'available_supply', u'percent_change_24h', u'id']

So yeah! You can do whatever you want with that.

Twilio

As for sending text messages through a python script, I wasn’t able to discern a clear way of doing this without another great API. So what I did (and you can expand on this portion if you want) is look towards Twilio. All you have to do after you sign up and register an account is confirm the numbers that you’re being used and do some simple cross confirmation from the cell device and Twilio.

After that, it’s pretty straightforward but you can use the Twilio API. The main things that you need are a Twilio account sid and a Twilio account authentication token.

I just stored this information in a yaml file (called api_keys.yaml) because those are really easy to deal with. Essentially, just create a yaml file with some of this pertinent information. Note that because I thought I might do some algo trading, I also configured this script to make sure that I was connecting to gdax… You can remove that functionality if it’s burdening the program.

twilio_account_sid: <sid>

twilio_auth_token: <auth_token>

gdax_key: <key>

gdax_api_secret: <api_secret>

gdax_passphrase: <passphrase>

And then yeah you’re good to send text messages (and also trade on GDAX algorithmically if you want to extend it a bit). It’s as simple as passing in the following information.

client = Client(key_dict['twilio_account_sid'], key_dict['twilio_auth_token'])

cryptos_to_get = ['BTC', 'ETH', 'MIOTA', 'XRP']

string_builder = get_crypto_market_info(cryptos_to_get)

for number in numbers_to_send:

mess = client.messages.create(

to = number,

from_= twilio_number,

body = string_builder)

I didn’t want to grab all of the crypto information. Too much information is overwhelming so I just specified the symbols of interest. Boom! You’ve got the basic underlying infrastructure to send text messages to your self about crypto information just by a python program.

Cronjob

But why stop there? Why not automate the delivery of these messages? This was something I had no experience with before Belvedere, but cronjobs are an incredibly useful tool for a developer to have. This is a way to schedule a task to be run routinely and automatically on either linux or mac operating systems.

If you’ve never scheduled any cronjob’s and you own a mac that you’re casually scrolling through this site on, then you can follow these steps.

Open up terminal and run,

crontab -e

Ok, so now you’re good to go for rigging up your own cronjob.

Formatting!

All cron jobs start with the following description. This is going to describe how often you want your actual job to be run. It’ll follow the following format (which can be found all over the palce). This one is good. But basically can be summarized like so:

<minutes> <hours> <dayOfMonth> <month> <dayOfTheWeek>

| | | | |- (0-7) - 0 and 7 both represent Sunday, or * for wildcard

| | | |- (1-12) - months, or * for wilcard

| | |- (1-31) - days, or * for wildcard

| |- (0-23) - hours of the day, or * for wildcard (local time! not UTC)

|- (0-59) - minutes of the hour, or * for wildcard

It’s about that simple. Again, the times are run in local time. The other thing is that the * is generally an indication for will take anything in. So it covers all possible options. Other things, is you can easily specify ranges or disjoin times. For example,

30 5,17 * * 1-5 # means all weekdays, at 530am, 530pm

is valid. See how you can specify 5,17 which selects only 5am and 5pm, and also just do a full range (1-5)?

So if you want to execute a python program what you’ll have to specify is your python path. So you can do

0 12 * * 1-5 /opt/local/bin/python <path_to_actual_file> <optional_program_args>

This should be good to go for automating your python script to run with regularity!

Why the tmp file?

Another interesting note. crontab -e edits users’ crontabs meaning that this is specified at the user level. This is not a system wide cronjob that will run regardless. The reason when you save out of this is that you’ll see it most likely stored in /tmp/crontab.<randomHash> is because this is actually pulling a copy of your user level cronjobs that are scheduled. It copies the crontab file to a temporary directory mainly for two reasons.

- Sanity check

- Preventing two users from editing the same file at the same time.

If you’re on OS, then where your actual cronjob is stored at the user level is in /var/at/tabs. Note however, that you’ll need to access this directory if you’re really trying to check out the ground source of truth for cronjobs (because this is protected information by the system… hence the copy over into a temporary directory). Anyway! This tangent was just for the more curious.

Printing to terminal during your program

So if you’ve got a cronjob running to execute this program one thing to be mindful of is printing out information during the program’s lifetime. What’s going to happen is the next time that you open up your terminal, your OS might say “You have mail” before printing our your normal bash prompt. This is fine - it just means there’s information from the cronjob that has been stored in your user mail file. To deal with this, nagivate to cd /var/mail. Once you’re here (if you’re seeing that you’ve got mail message), you should have some file that you can read that will either tell you what you’ve printed our or any errors that occured when you run your program. Another thing to be mindful of is that your working directory of the program is going to be inheritely different because it’s being executed from your home directory. So that means that you need to take this into account when you’re writing your cronjob programs - if that’s relevant that is.

Terminology

I’ve been flipping between cronjob and crontab, but there’s a rather important distinction. Cronjobs are what you put into your crontab. It’s really that simple. Crontab is the tab that holds all of your cron jobs.

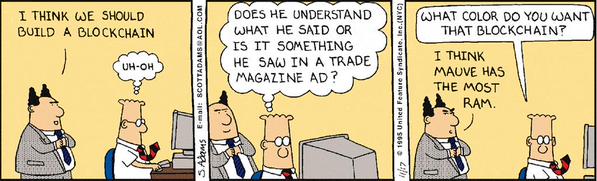

Putting it All Together

This was a fun little project to code up and to gain some experience in some things that I’m not super familiar in. I hope that reading it has been a helpful dive and hopefully inspired you to automate either some information or useful jobs that you’ve been thinking about. As always, please let me know if there’s anyway to improve my code or anything I can help you with. Again, feel free to check out the corresponding code. I’ll leave everyone with another great comic.